A Healthy Pipeline: Delivering Australia’s Hospital Infrastructure

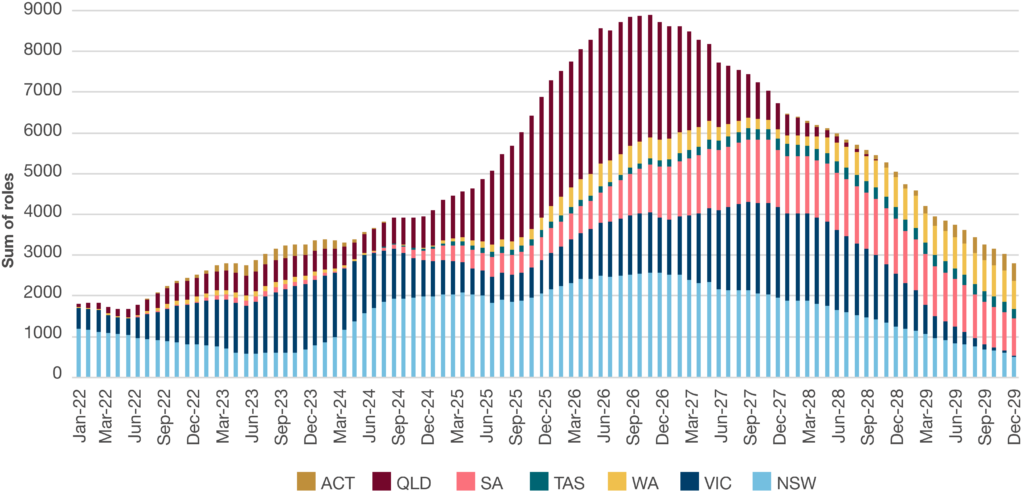

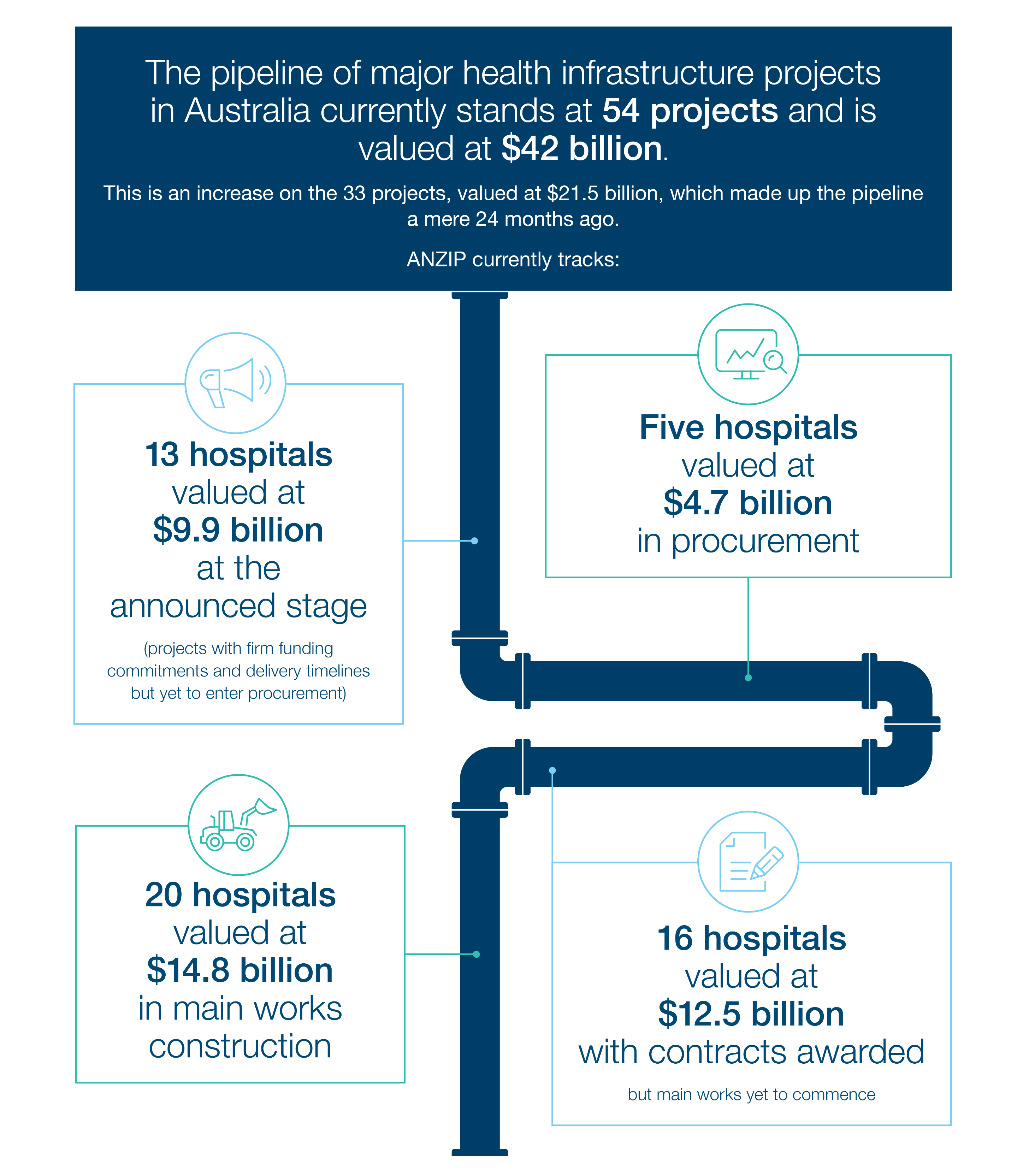

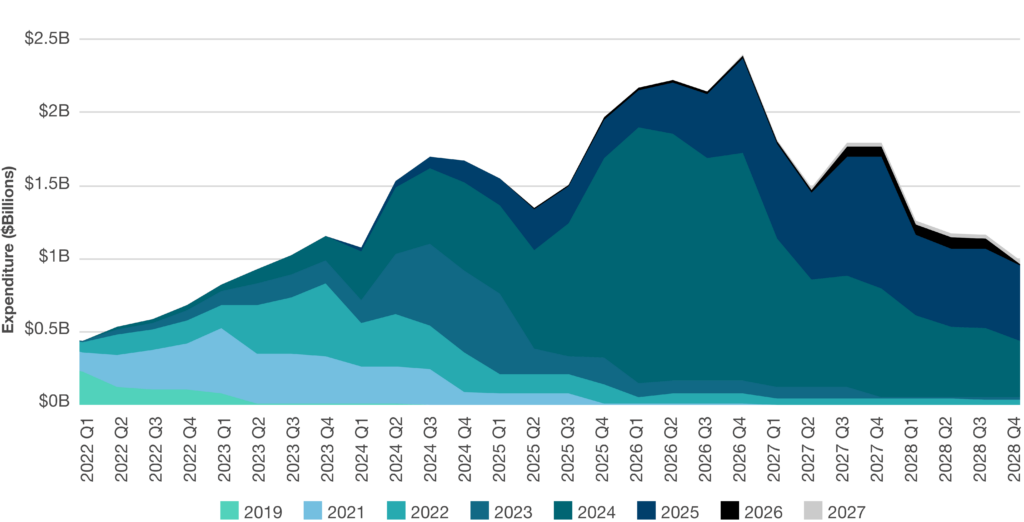

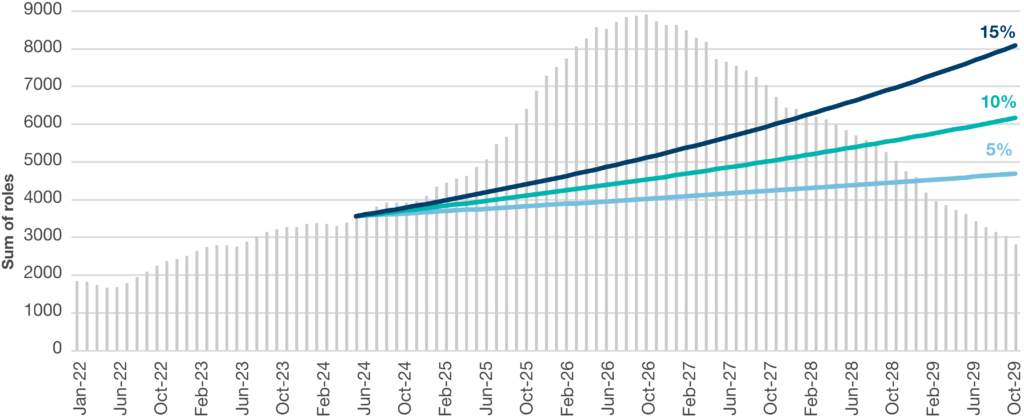

Infrastructure Partnerships Australia has released new research – A Healthy Pipeline: Delivering Australia’s Hospital Infrastructure. The report introduces a comprehensive health infrastructure trade demand model to illustrate the scale of the pipeline and the levels of trade resources, particularly the specialist and skilled trades, required to deliver it.

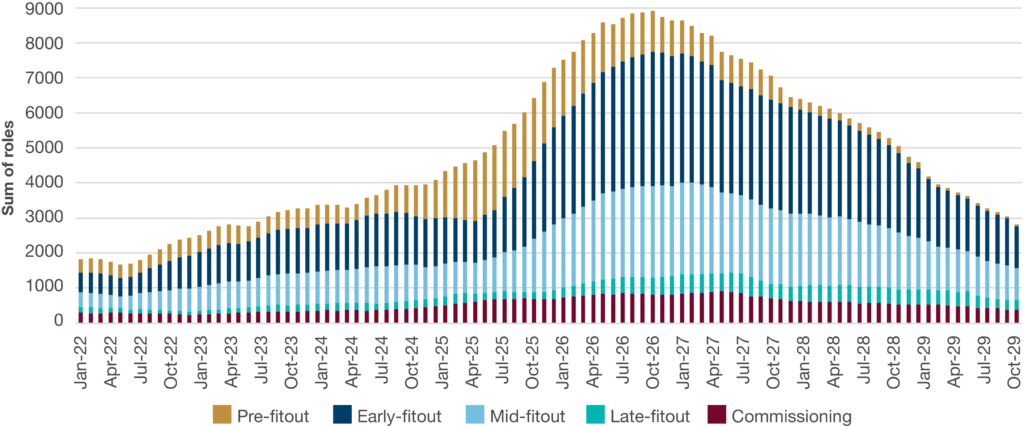

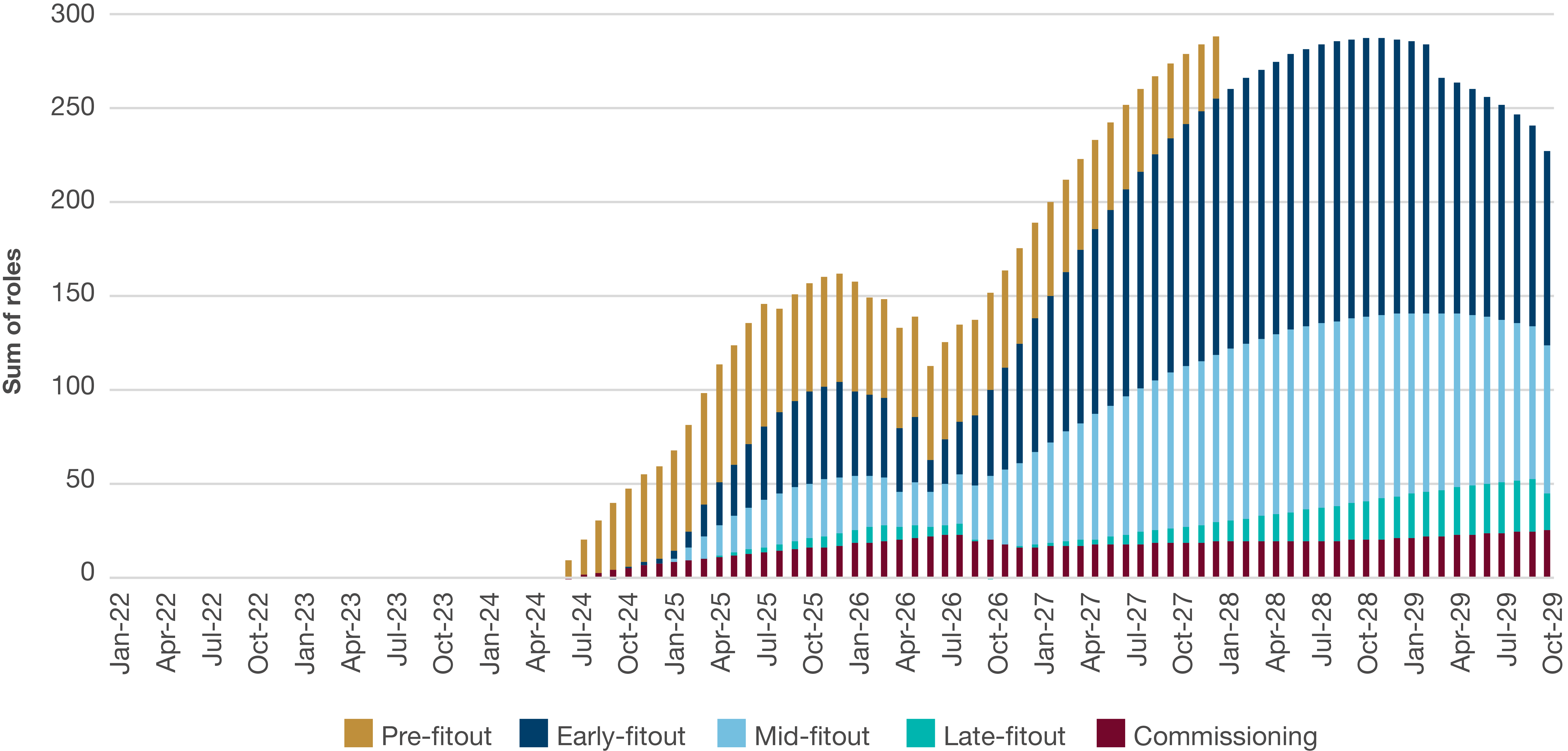

Infrastructure Partnerships Australia has developed a comprehensive health infrastructure trade demand model to illustrate the scale of the pipeline and the levels of trade resources, particularly the specialist and skilled trades, required to deliver it. It is clear from this work that the current volume and sequence of Australia’s health infrastructure pipeline will result in extended periods where the demand for highly technical and specialist occupations required far outstrips the supply available.

At its peak in late-2026, the projected volume of labour required to deliver the hospital pipeline will be two and a half times today’s level. To meet this peak, compound annual growth in the health infrastructure market would need to increase eightfold annually on what has been achieved over the last decade.

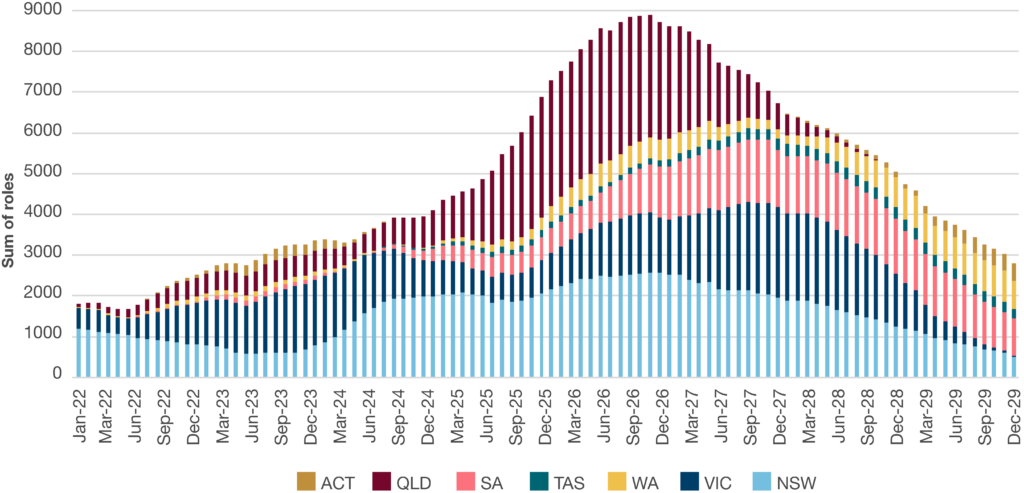

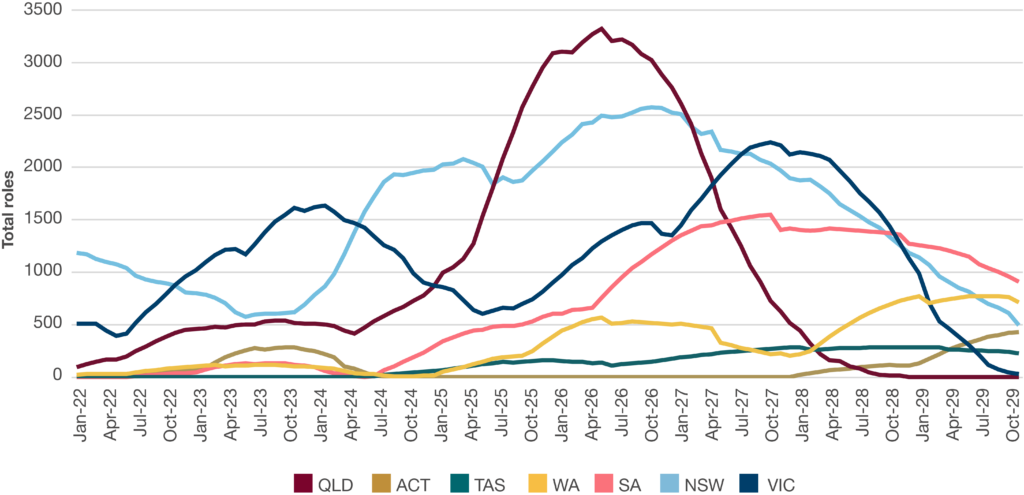

While all jurisdictions will require additional resources to deliver their pipelines, they each face unique challenges to do so, with some requiring more rapid uplifts and higher volumes of new labour than others.

Even when optimistic projections are applied to achievable levels of growth in the workforce, it would be exceedingly difficult to deliver the pipeline to its current schedule. There is a functional ceiling in Australia’s health infrastructure market that governments and delivery bodies must be aware of for future health infrastructure capital planning. Periods of undersupply in the market will result in suboptimal outcomes for all stakeholders, with inefficiencies leading to higher costs, longer construction times and ultimately less effective health services for end-users.

Governments and delivery bodies can ease near-term pressure in the pipeline by revisiting project scopes and timeframes to ensure the deliverability of their respective pipelines within prevailing market conditions. A rescoped pipeline will address the immediate challenge of ensuring projects can be delivered without significant cost or time blowouts at the expense of taxpayers.

In the longer term, reform measures should be undertaken to minimise the reoccurrence of future supply-demand pressure points. This can be achieved through addressing demand side pressures by improving pipeline planning and capital allocation models. Investment in the workforce that supports skills training and development for domestic and overseas workers should be implemented to address supply-side factors.

Challenges to delivering the existing pipeline

There are a number of challenges to delivering the existing pipeline on-time and in-budget, including competition for labour from other sectors, intrastate resource competition and shortages across the specialised trades and skills required to deliver hospitals.

Competing demand for skilled labour

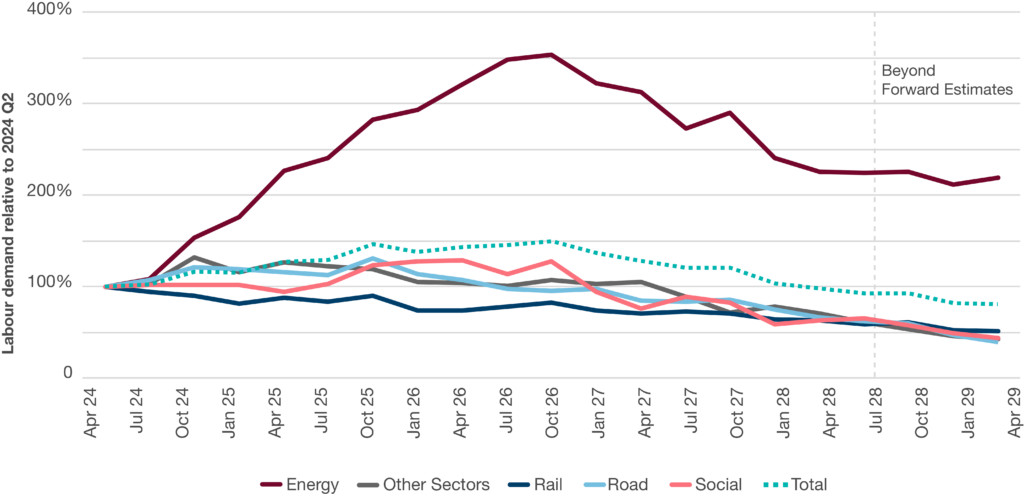

Further compounding the labour challenge facing the health infrastructure pipeline is that it will be delivered within a wider landscape of an ambitious infrastructure pipeline across renewable energy, defence, transport and other social infrastructure. Labour demand for all ANZIP infrastructure projects is expected to increase by 50 per cent between now and 2026, creating concurrent skills deficits across non-health domains.

While not being entirely transferable, there are some skills required in hospital construction that intersect with other industry segments, meaning that there will not only be competition for resources across jurisdictions but also across sectors.

Figure 4: Forecast labour demand by sector, across infrastructure

Source: Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

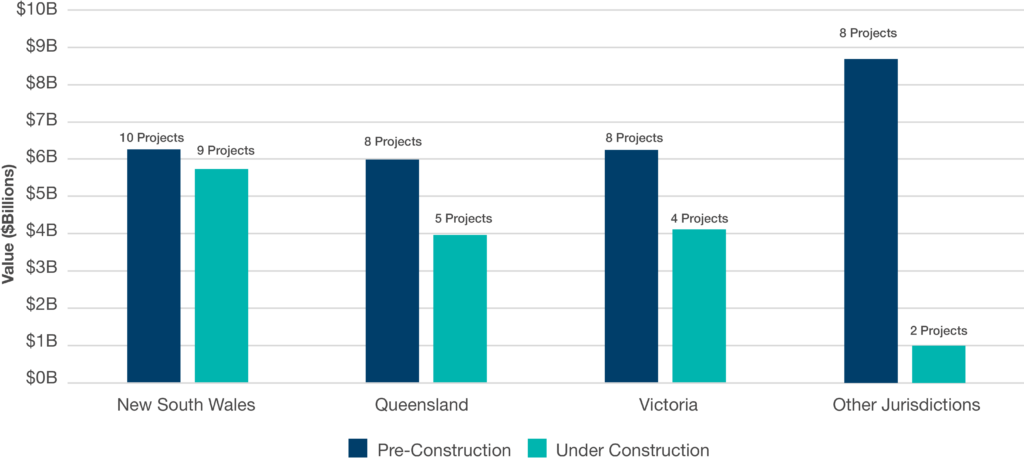

A geographically diverse health infrastructure pipeline

Alongside its rapid expansion, the health infrastructure pipeline is also experiencing a geographical shift away from jurisdictions with historically steady pipelines. States such as NSW and Victoria – owing to their large populations – have been able to develop stable volumes of health infrastructure work over time. These states have taken a long-term approach to building industry capability, enabling them to be more responsive to increases in demand from within and outside their jurisdictions.

Conversely, other states and territories have been rapidly scaling up their pipelines for one-off or limited numbers of projects to be delivered over relatively short timeframes. Delivering the health infrastructure required to meet population requirements is a necessary action of responsible governments. However, the concurrent nature of these expansions and the relative inability of these jurisdictions’ markets to react to resource increases in other jurisdictions leaves their projects more vulnerable to cost overruns and delayed delivery. If the pipeline is to be delivered to its current schedule, it is these jurisdictions who will be most exposed to this vulnerability.

Queensland is scheduled to deliver 15 projects valued at $11.2 billion over the next four years through its Capacity Expansion Program, while both South Australia and Western Australia will be mobilising and developing capabilities to deliver some of the largest health infrastructure projects ever constructed in their respective jurisdictions. Further, these parallel expansions do not provide the sufficient, steady pipeline of work which enables major subcontractor firms to build new capability or to reprioritise away from existing client/contractor relationships and reliable volumes of work in other jurisdictions. Such projects will be competing for even scarcer subcontractor resources.

To add a further layer of complexity, 20 per cent of the ANZIP health infrastructure pipeline will be delivered in regional locations. Delivery of health infrastructure in regional and remote areas offers a range of labour and supply chain complexities additional to metropolitan projects. Workforce attraction is more challenging in regional locations where amenities such as accommodation may be insufficient to cater for workers supplementing local labour. In these instances, contractors may be required to deliver purpose-built temporary accommodation sites at an additional cost to the client and posing risks to a project’s social licence. Additionally, incentivising workers to join regional project teams when a robust pipeline of metropolitan projects exists can be challenging, indicated by the burgeoning regional energy pipeline.

Differing labour mobility profiles for individuals and firms

The geographical shift in the location of new projects to jurisdictions which traditionally have not had such significant pipelines adds additional workforce challenges. Jurisdictions with emerging pipelines typically have a less consolidated technical and specialist skilled workforce readily available for hospital delivery and will need to be supplemented with skills from other jurisdictions.

When considering relocation to a different state for project(s), organisations and individuals will have different factors and motivations to weigh up.

Organisations

There are a number of factors that impact organisations’ willingness to relocate or expand their business to new states, territories or regional areas to deliver new pipelines of work:

• Organisational appetite to grow their national footprint

• Existing corporate footprint and on-site capabilities in new jurisdictions

• Ownership structures and access to expansion capital

• Level of prequalification required in the new jurisdiction (contractual or technical prequalification)

• Differences in industrial agreements in the new jurisdiction compared to their current location

• Pace at which subcontractors can identify and hire workforce and subcontractors in the new location

A lack of appetite to establish a presence in a new jurisdiction can have a particularly limiting effect on those trades that only have a handful of existing tier one subcontractors capable of delivering the largest scale projects. Should those subcontractors choose to not establish themselves in a new jurisdiction, the jurisdiction’s overall capability to deliver will be significantly constrained.

Individuals

Individuals with sought-after skills – who are not otherwise constrained – will reasonably seek out projects and locations which offer the highest remuneration and most amenable living circumstances. With the volume of work available across the country higher than the supply of labour, individuals can choose where, and on which projects, to work.

Owing to varying industrial relations practices, remuneration for the same occupation in some instances can differ by over 30 per cent between neighbouring jurisdictions. These differences can be further exacerbated in regional or remote locations where limited access to quality accommodation and appropriate amenities can further reduce the incentive to relocate from higher-paying jurisdictions.

There are several trades required for specialist roles in hospital construction with a limited number of individuals possessing the appropriate skills and experience. These individuals are price makers who hiring organisations are entirely dependent upon securing for their project – there are few alternatives to source these requisite skilled individuals.

An individual with an in-demand set of skills seeking out higher remuneration for their labour is not a negative outcome. Rather, it is incumbent on state treasuries, health building authorities and the private sector to ensure they appropriately plan their pipelines to maximise deliverability and avoid additional costs being passed onto taxpayers, who also represent the end-users of these facilities.

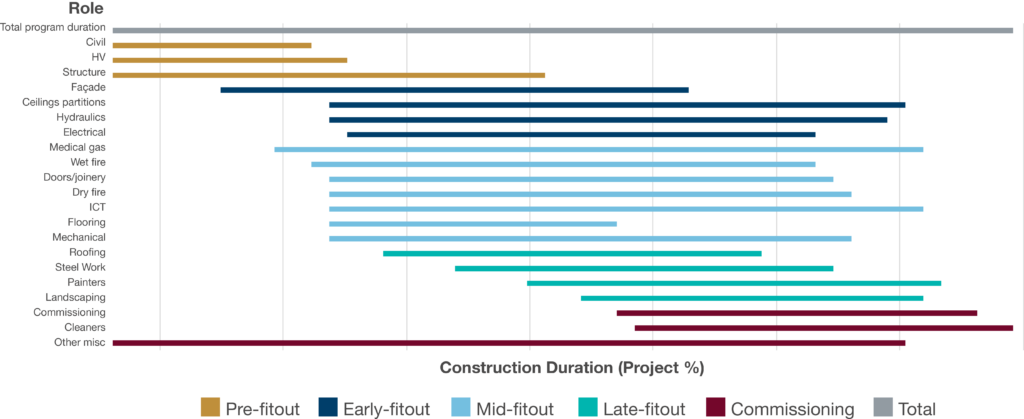

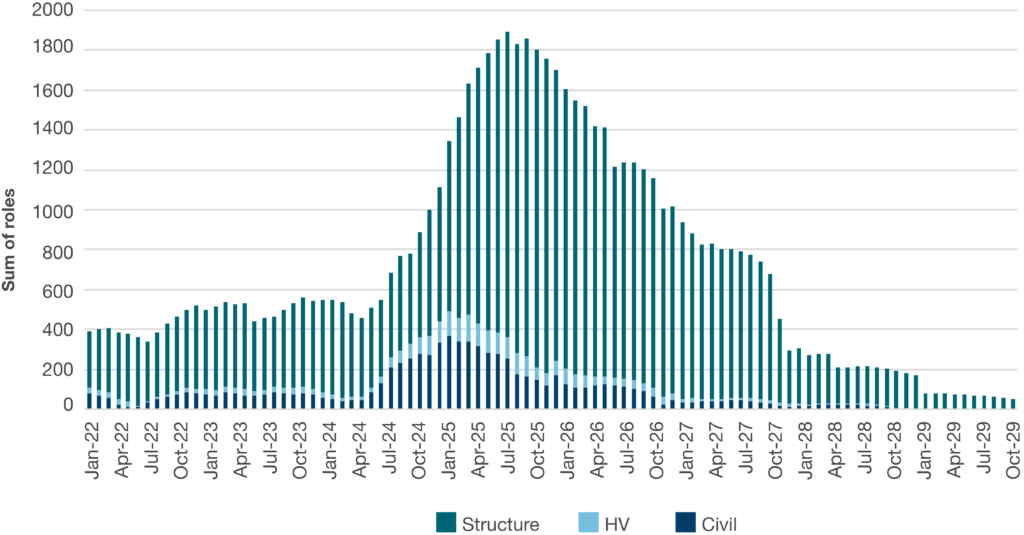

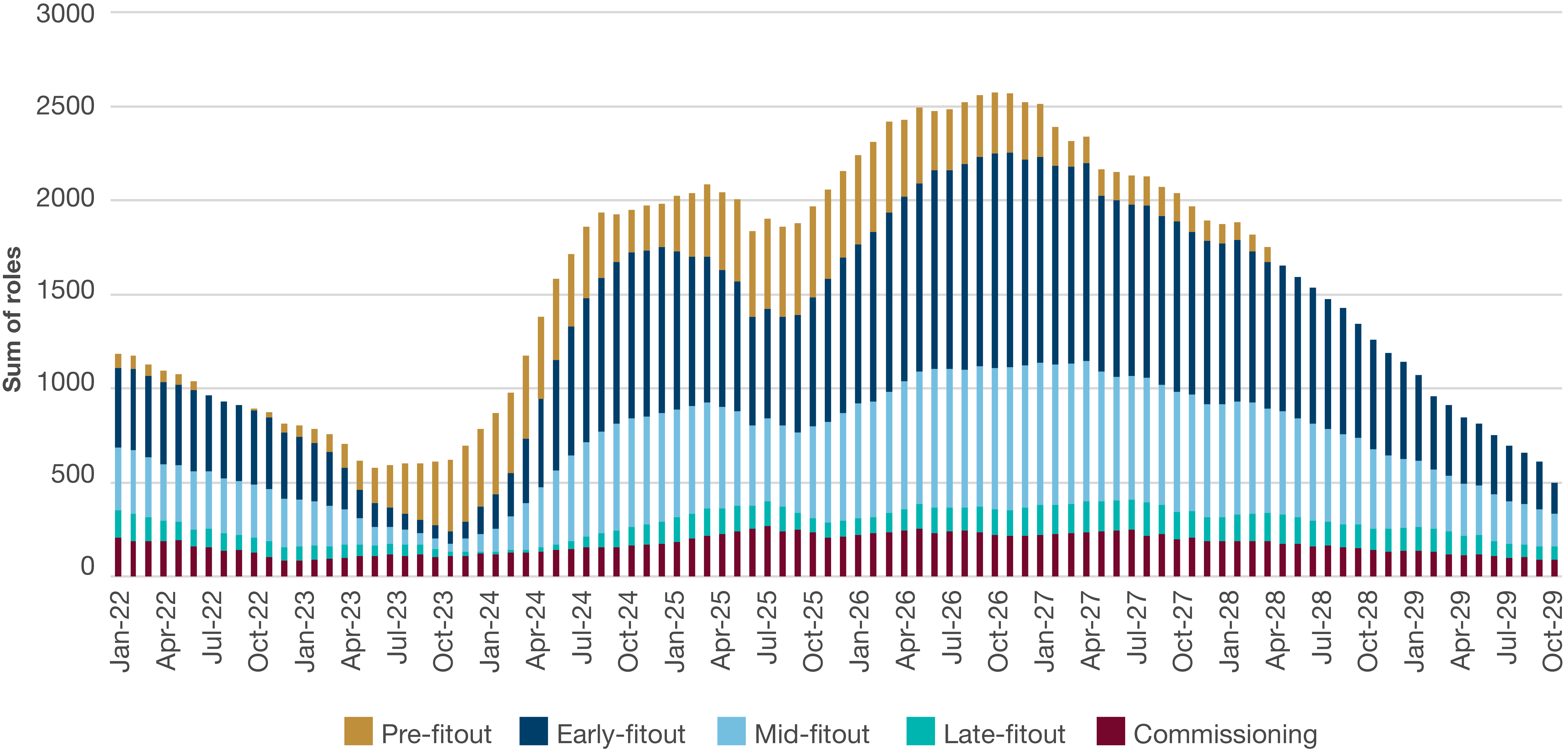

Pre-fitout phase

Figure 7 highlights that from current levels, pre-fitout resources will need to more than triple at their peak demand in August 2025. A key component of the pre-fitout phase is the delivery of formwork for structural construction. Stakeholder engagement identified that there are currently less than 10 firms in the country able to deliver the formwork required for hospitals and that these firms are already operating at capacity.

Consequently, they have little incentive to travel across states to take on additional work. Individual mobility is also limited in this trade, with workers generally opting to remain in their home states rather than travel for work.

There is a degree of transferability across some skills involved in the pre-fitout stage meaning there is a wider base to draw from, however, there will be competition from other assets across infrastructure.

Figure 7: Forecast trade demand over time, pre-fitout phase

Source: Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

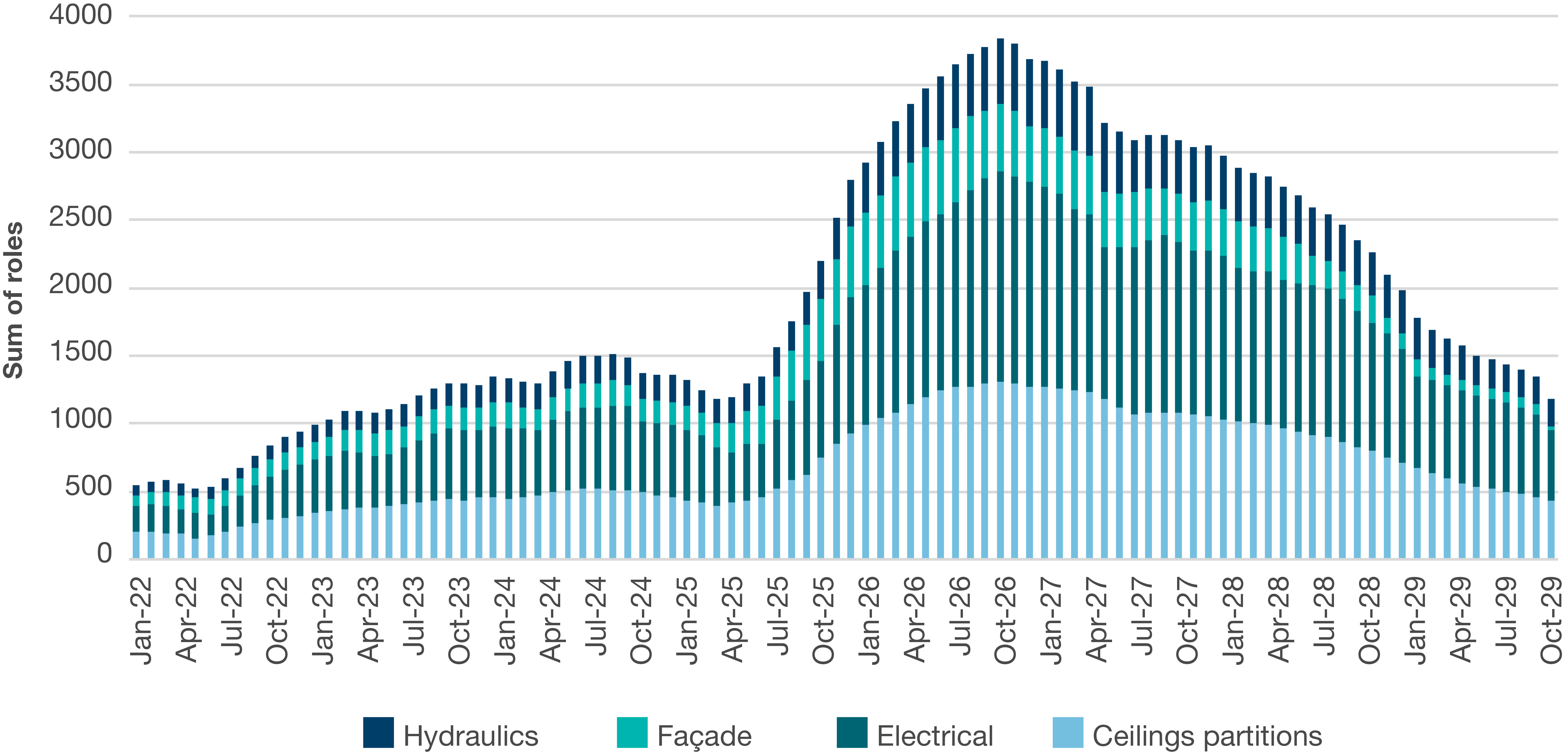

Early-fitout phase

The forward program sees a 168 per cent increase required for electrical skills by November 2026 and a 142 per cent increase in hydraulics requirements in the same period. Hydraulic and electrical skills are in severe shortage today, as are plasterboard sheeting resources. There is a very limited pre-existing pool of firms operating in these trades in the health infrastructure sector. The peak in demand for both of these trades is expected across 2026 and 2027.

Stakeholder engagement identified that shortages are particularly acute for on-site mechanical and electrical installation services. These trades are particularly susceptible to competition from other infrastructure industries, including transport and pumped hydro tunnelling, and defence.

General electrical training does not equip an individual to deliver the work required for hospitals. It would take a full three-year project cycle to upskill a general licenced electrician to be a hospital electrician.

Figure 8: Forecast trade demand over time, early-fitout phase

Source: Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

Mid-fitout phase

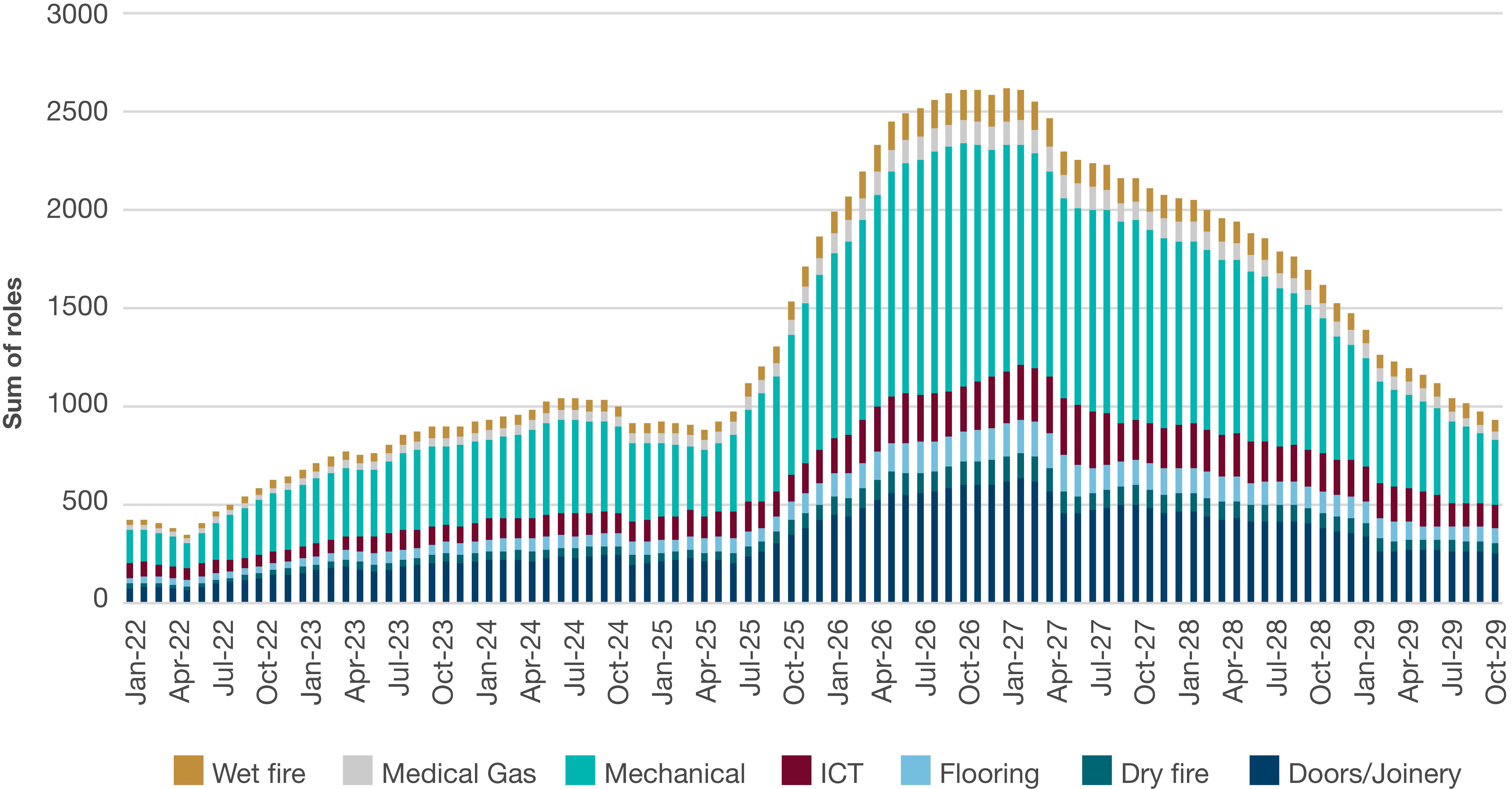

Resource requirements for all trades in this project phase require significant upscaling by the peak around February 2027.

Whilst small in overall gross numbers, flooring trades (vinyl layers in particular) and medical gas resources are on project critical paths and delays in installing floors and medical gas infrastructure will bring wider construction delays leading to inefficient project delivery.

Across vinyl laying/welding, there are low numbers of qualified individuals who can undertake this complex work, whilst demand is growing for vinyl installation. There are also challenges with the supply of materials and costs of importing products from overseas. To give one indication of the scale of work facing this trade – 167 kilometres of vinyl will be required to be delivered under Queensland’s Capacity Expansion Program.

There are limited numbers of plasterboard subcontractors for plasterboard installation – which are generally small organisations – with some recently entering administration. Furthermore, few are able to access trading credit from sheeting suppliers, resulting in contractors increasingly having to supply the materials to subcontractors.

Stakeholders also identified limited design capacity for medical gases (in-house and outsourced), resulting in a near monopoly. Additional difficulties are also being faced due to challenges in accessing certified on-site installation labour and supply challenges with tanks and equipment.

Figure 9: Forecast trade demand over time, mid-fitout phase

Source: Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

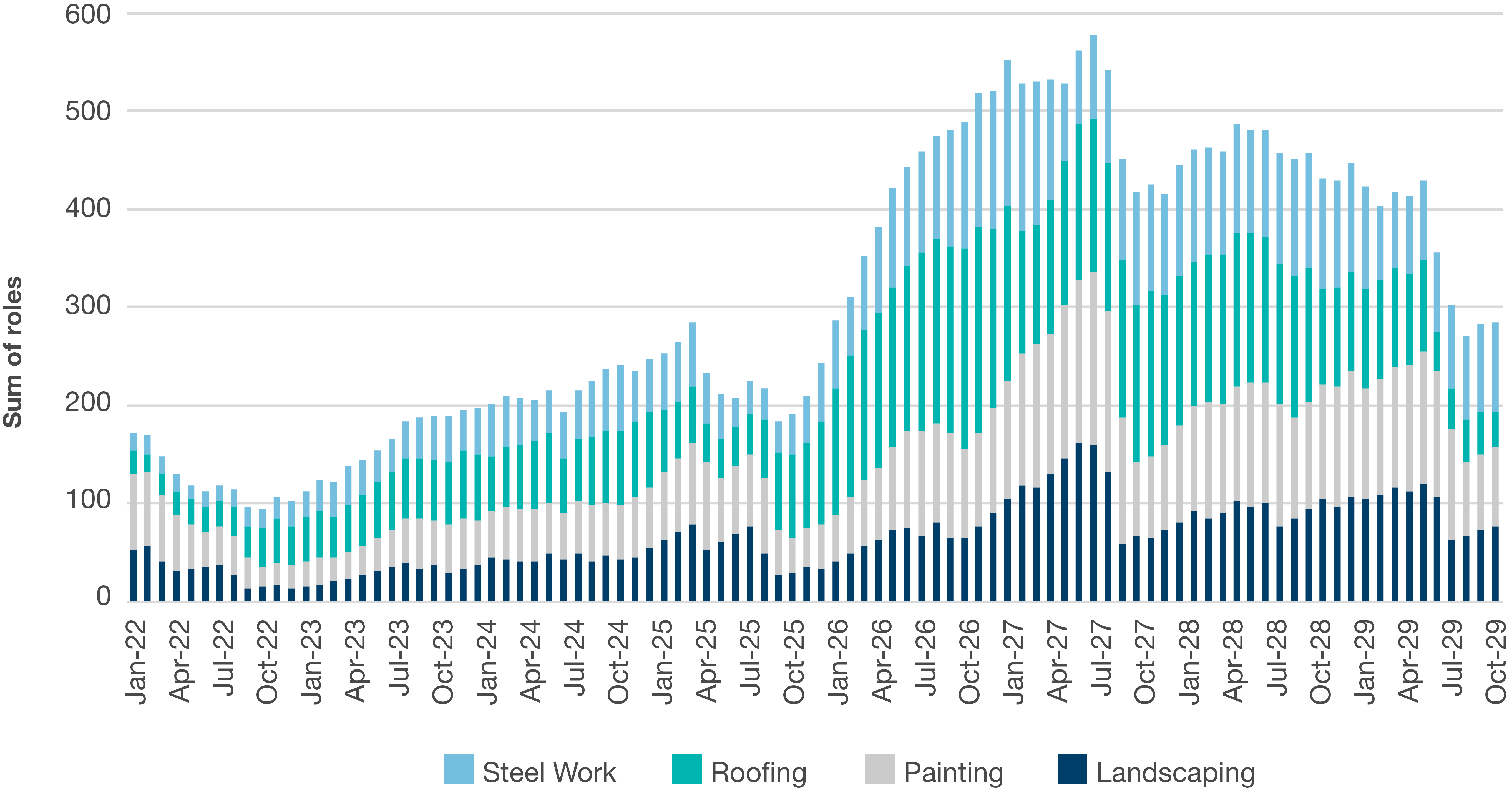

Late-fitout phase

As with all other skilled areas, growth in the trades required for late-fitout works will be needed to deliver the forward pipeline. Resource requirements for the late-fitout phase will peak by August 2027, requiring a 166 per cent increase on today’s levels.

For this stage, the trades and skillset required are typically more generalised than what is required for other stages and it may be easier to draw resources from other infrastructure asset classes.

An uptick in demand for these skills will likely result in constraints, particularly in the broader context of a major residential building focus.

Figure 10: Forecast trade demand over time, late-fitout phase

Source: Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

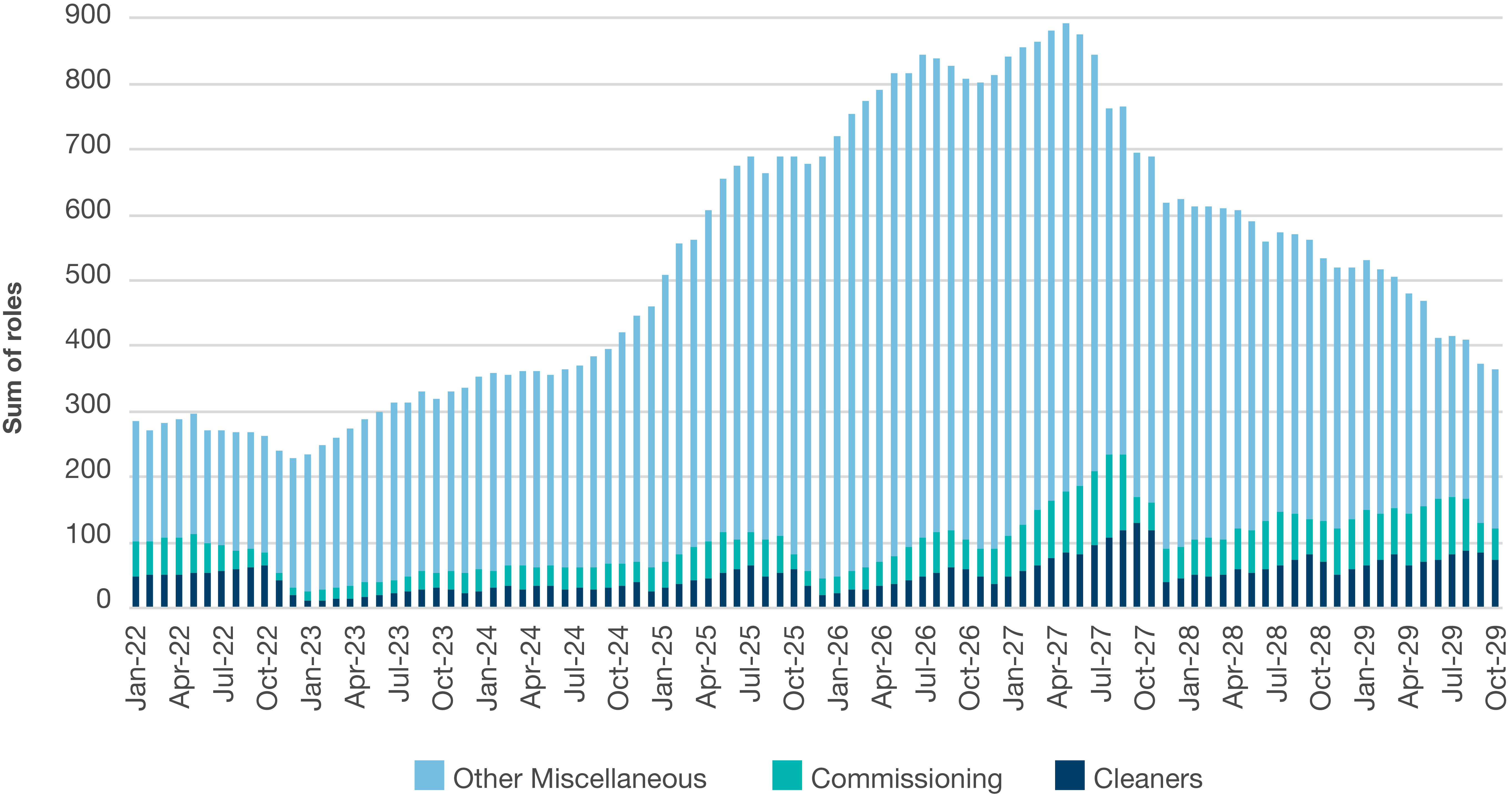

Commissioning phase

Commissioning and testing skilled resources are in short supply. While the number of roles required for the commissioning phase is smaller than in other phases, a significant uplift in volume is required to meet demand and allow health infrastructure projects to reach completion.

Experienced commissioning teams allow for efficient translation from construction into operation, and to achieve rapid certifications and regulatory signoffs before a hospital can move into operations.

Figure 11: Forecast trade demand over time, commissioning phase

Source: Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

Planning

Recommendation: Undertake a comprehensive review of the approach to capital allocations for health infrastructure delivery to provide certainty to local health districts on future funding allocations and support a more modestly staged approach to project delivery.

There is an opportunity for governments to avoid future supply-demand imbalances through facilitating a more staged approach to project delivery, by adopting a longer-term approach to capital allocations to health districts.

Currently, there is a disconnect between the longer-term clinical planning undertaken at a local health district level and the way that capital is allocated. Local health districts usually receive sporadic or periodic allocations of funding to address district demands, without certainty on future funding allocations over medium- and longer-term horizons. This approach can lead to local health districts progressing projects designed to meet forecast clinical service needs all at once. Such an approach risks projects being planned and announced that significantly exceed short-term clinical requirements and – due to their scale and complexity – consequently have potentially unnecessary heightened delivery risks. This is seen through the recent rise in health infrastructure mega projects, which can in part be attributed to the lump sum funding approach. These larger projects come with increased capital expenditure costs and delivery complexities, as well as heightened operational and maintenance costs post-delivery. Larger projects can also face additional challenges such as ensuring they are appropriately resourced once operational. Such challenges underpin the need to ensure assets are appropriately sized from a delivery and operational perspective.

A holistic review of the (formal and informal) capital allocation structure should be undertaken with an objective of providing more certainty to local health districts on future funding allocations over a longer horizon. Quality clinical service planning, coupled with medium-term capital delivery masterplans, could establish a more modestly staged approach to project delivery.

This would lead to projects that are appropriately sized, or delivered in staged approaches within current prevailing market conditions, with less complexities and upfront costs. A staged approach to larger projects has been effectively deployed in health infrastructure previously, where brownfield projects have undergone progressive upgrades. Some examples of this approach to staged delivery include the redevelopments of St George Hospital and Nepean Hospital in NSW.

Longer term funding certainty could also underpin a longer-term planning approach for asset management. Governments should look to optimise the productivity of existing assets and minimise tertiary hospital demand where appropriate. The supply of services from existing assets can be increased through efficiency measures like modern methods of care, digital adoption, and state and federal healthcare policy alignment. Reducing tertiary hospital demand could see increased provision of allied and preventative health services and public health campaigns. Bringing the supply and demand of existing tertiary hospital services closer to equilibrium would have the consequent effect of lowering the demand for new health infrastructure. While these measures may not decrease the overall quantity of projects in the pipeline, it will extend the timeline in which they require delivery, giving the public and private sectors an opportunity to better deliver them.

While this staged approach to project delivery lends itself more readily to brownfield redevelopments, with 77 per cent of the megaprojects currently in the pipeline being greenfield developments there is ample opportunity for larger greenfield projects to be delivered across multiple stages.

Design

Recommendation: Reduce project cost and time overruns by opting for simple project design and using contract terms to minimise ‘in-construction’ design changes.

Ensuring efficient, simple project design can alleviate unnecessary market pressures by facilitating a smoother delivery process and optimal clinical outcomes. Complex design features, while enhancing architectural outcomes, can impact costs and delivery times. This is not to say that future hospital builds should be devoid of human-centred and salutogenic (i.e. promoting wellness) design qualities – healthcare spaces should support the optimum outcome for end users and be high quality workplaces for healthcare workers – however, a careful balance between developing creative environments and affordable buildings must be struck. The Australasian Health Facility Guidelines provides guidance on standardisation, modularisation and simplicity of functional design and layouts for health infrastructure.

Through our stakeholder engagement activities, it was evident that one of the most significant sources of project delays is ‘in-construction’ changes to project design. In order to ensure that projects are delivered within their planned cost and timeframes, certainty of planning and design from the outset is key. Despite the fact that decisions made after construction commencement are often in a proactive manner, any scope changes risk leading to an escalation in delivery costs or impacting delivery timeframes. Governments can use contracting approaches to consolidate a project’s design elements prior to construction. This then acts as a commitment device between parties to structurally limit potential of divergence from agreed outcomes.

Procurement

Recommendation: Consider all procurement options available on a project-by-project basis to deliver optimal outcomes for taxpayers.

Procurement models can be used to appropriately align risk during project delivery. No one procurement model can, or should, serve as the universal method for health infrastructure project delivery. To this end, it is crucial that procurement teams consider all feasible models in order to identify the optimum method for any given health infrastructure project within prevailing market dynamics.

In recent times, some jurisdictions have opted for cost reimbursable procurement models, namely through appointing Managing Contractors for health infrastructure projects. Lump sum procurement models are also typically deployed for health infrastructure. Beyond these more traditional forms of procurement, there are other recent examples of success in the utilisation of fixed price delivery models delivered via Public Private Partnerships (PPPs).

Infrastructure Partnerships Australia’s 2020 Measuring the Value and Service Outcomes of Social Infrastructure PPPs report found that social infrastructure PPPs delivered substantial benefits to providers and users of health infrastructure, alongside other social infrastructure asset classes. Supported by its findings, the report recommends governments – where supported by business case analysis – continue to secure new PPP contracts for service providers and their communities to meet current and future social infrastructure needs.

Irrespective of the model selected, ensuring the procurement process is open, interactive and transparent will facilitate the most efficient project delivery well before the commencement of any on-site works.

To ensure a continued supply of skilled labour, governments should undertake measures to attract and retain domestic and overseas workers.

Similar to skills requirements for the broader infrastructure sector, a two-pronged approach is necessary to both attract and retain overseas talent and maximise domestic skill capabilities. A broad-ranging policy environment that supports both skills training and development for domestic workers, combined with visa reform that attracts and retains highly skilled workers from overseas, is a pre-requisite to ensuring a continued supply of the technical and specialist skills required to deliver health infrastructure.

Migratory Reforms

Recommendation: Account for specialist labour and skills requirements as part of wider migratory reforms.

Reforms to Australia’s migration system that closer align with the demand for Australia’s labour market will assist all sectors. Skilled migration should not be viewed simply as a means to temporarily plug a labour gap; it is an opportunity to attract future Australians to our shores. With the availability of skilled migrant construction workers lagging behind the growth of the workforce, any increase to construction migration would have a direct benefit to hospital delivery.

Australia has a number of mechanisms to attract and retain the specialist and technical skills required for hospital delivery. This includes national skills lists, which make select visa types available for overseas workers who are qualified to work or train in determined skilled occupations in Australia. Such lists should align closely with the skilled shortages identified around hospital trades, and these workers should be prioritised and fast-tracked for approval with appropriate pathways to permanent residency.

To this end, examples of specialist and technical skills identified as being on the critical path for health infrastructure delivery include:

- Hydraulic specialists

- Vinyl welders

- Mechanical and electrical services – healthcare delivery

- Medical gas technicians and fitters

- Wet fire technicians

- Dry fire technicians

- Commissioning

Domestic Capabilities

Recommendation: Invest in domestic capabilities to underpin the future supply of requisite skills in the Australian market.

As Australia’s population continues to grow and age, future-proofing the health infrastructure construction workforce will also require reform to skills and training regimes. By acknowledging the highly technical and specialist skills required by hospital construction, state, territory and Federal governments should ensure workers both new and existing are incentivised to pursue in-demand skills.

Additionally, governments have an imperative to enable opportunities for an emerging labour force to engage in the training and education required for in-demand skills. This is by no means a short-term solution, however, it will enable the long-term security and stability of the future domestic skills base.

Investment in domestic capabilities should be set within a broader agenda promoting optimal productivity settings across the sector.

Appendix – Trade Demand by Jurisdiction

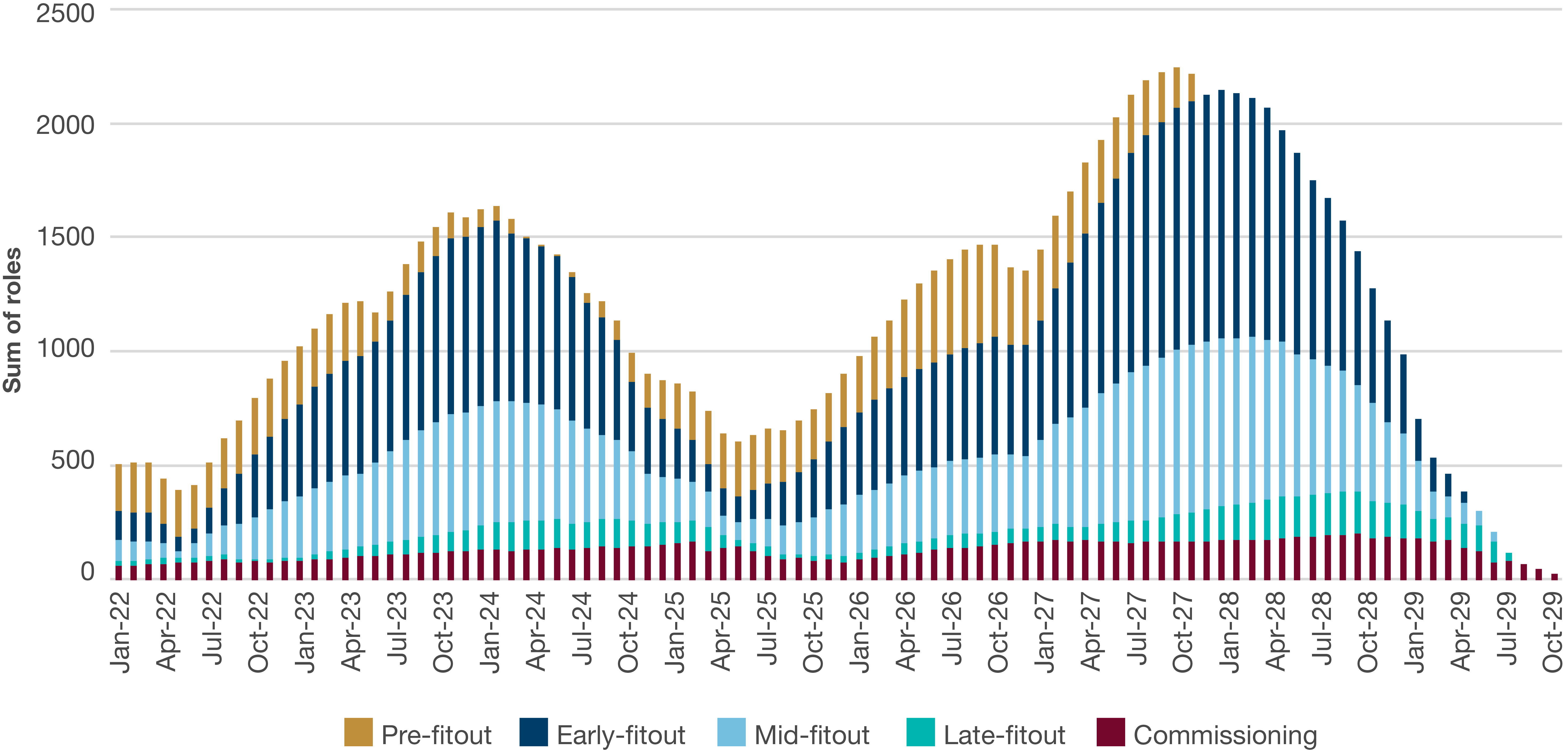

Figure 15: NSW health infrastructure trade demand, by project phase

Source: Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

Figure 16: Victoria health infrastructure trade demand, by project phase

Source: Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

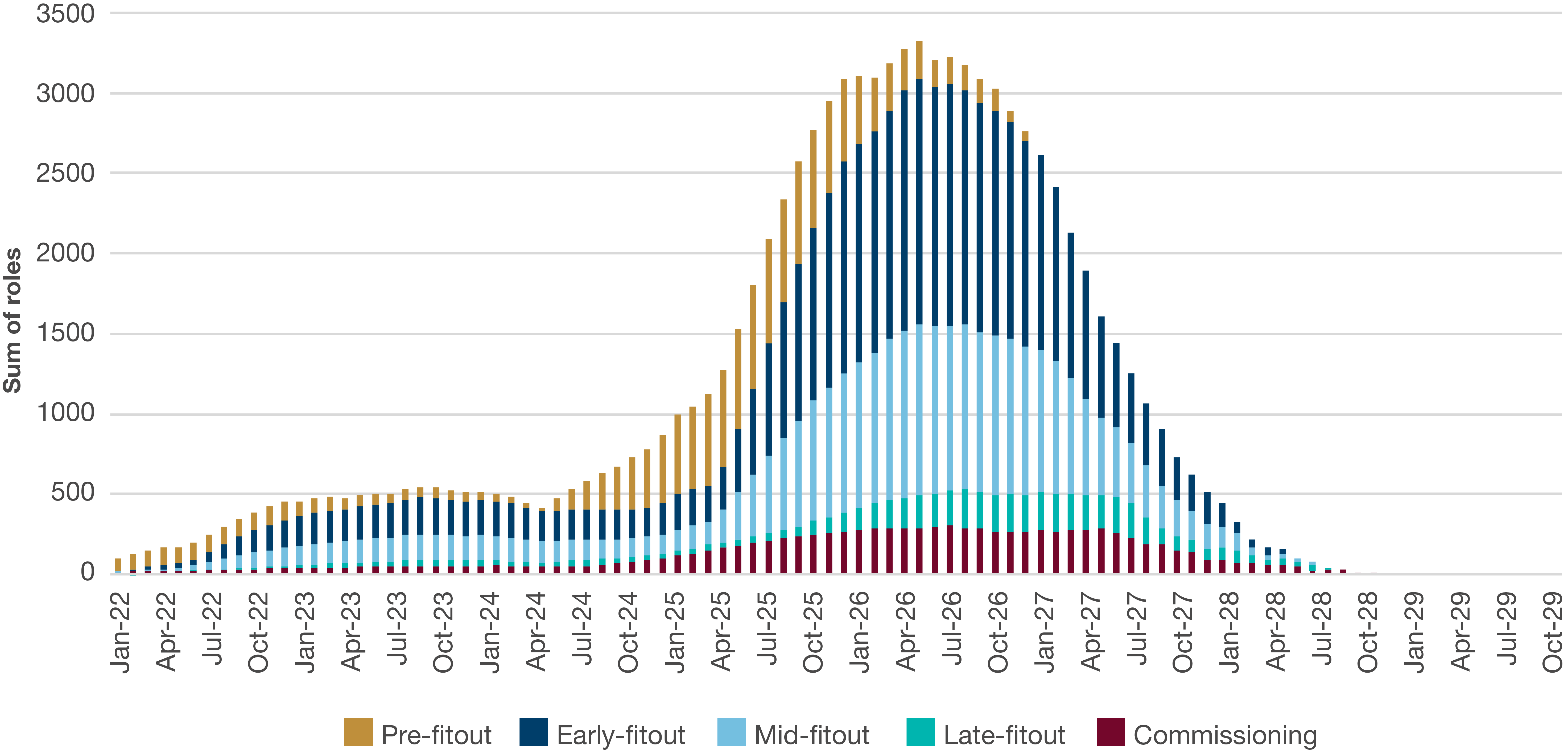

Figure 17: Queensland health infrastructure trade demand, by project phase

Source: Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

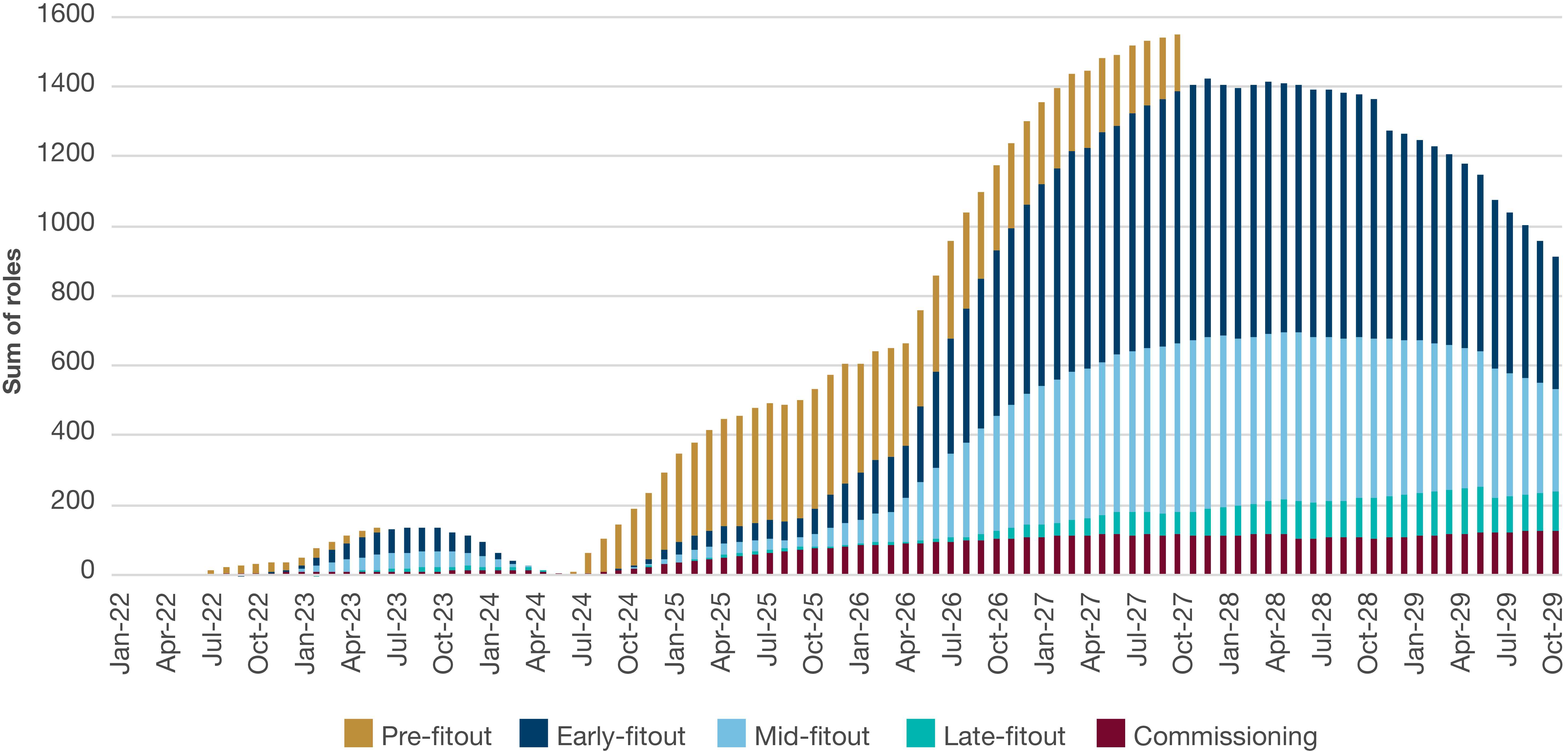

Figure 18: South Australia health infrastructure trade demand, by project phase

Source: Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

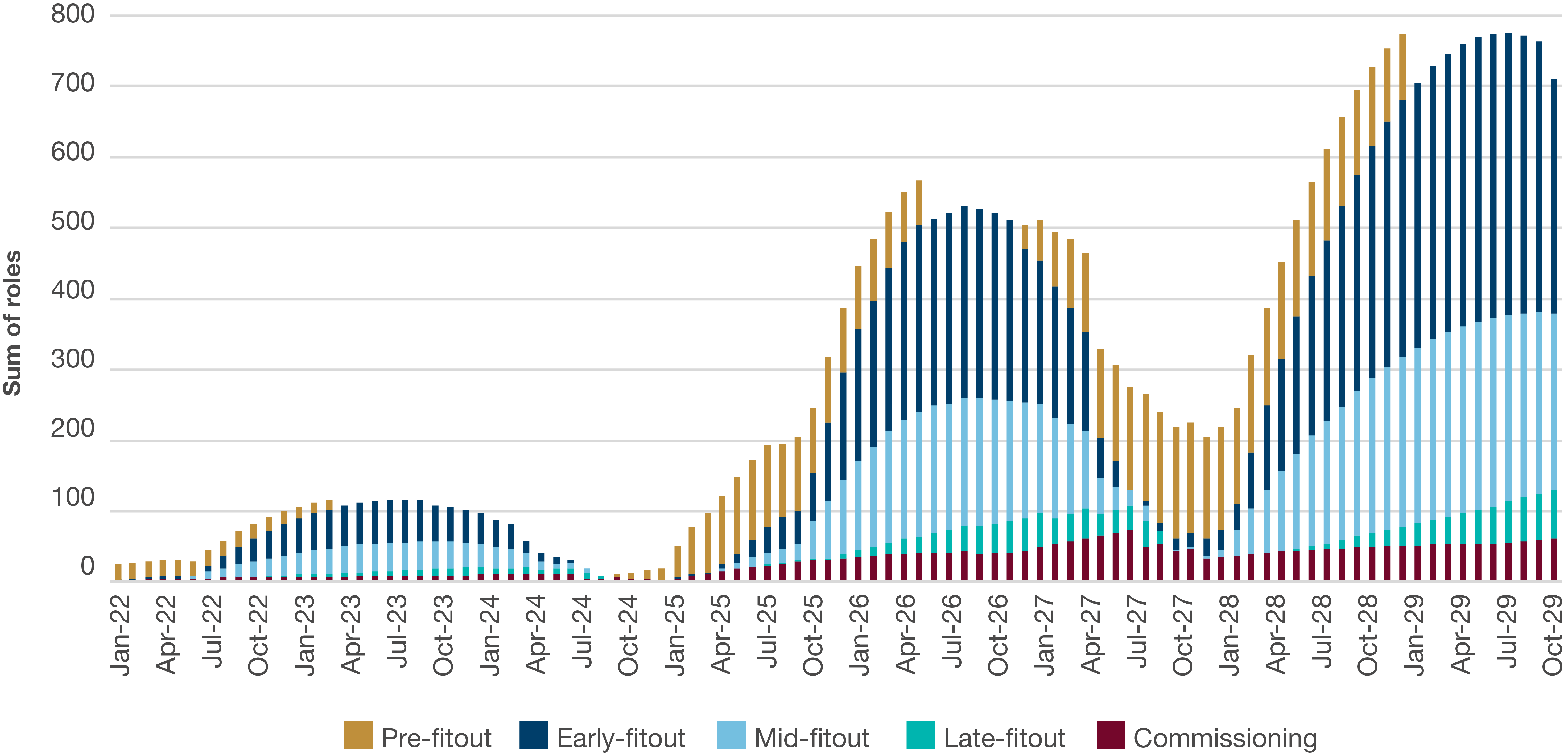

Figure 19: Western Australia health infrastructure trade demand, by project phase

Source: Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

Figure 20: Tasmania health infrastructure trade demand, by project phase

Source: Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

Sign up for more Infrastructure Analysis

Sign up for our popular weekly Infrastructure Report newsletter and keep up to date on all the latest developments in the sector.

Sign Up