Decarbonising Infrastructure

This report sets out a high-level assessment of the policy action required to decarbonise Australia’s infrastructure sector, across its asset classes. It covers energy, transport, and asset management during construction, operation and waste.

Video Snapshot

Australia needs to decarbonise, and infrastructure has a major role to play in driving us towards a zero-emissions future.

Our Infrastructure Carbon Footprint

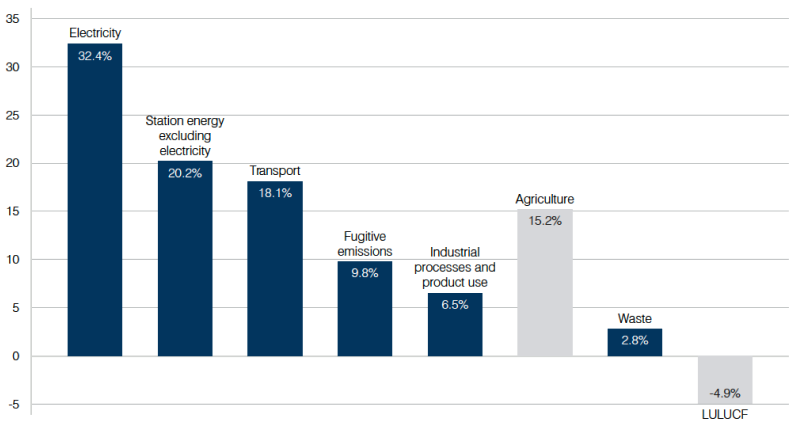

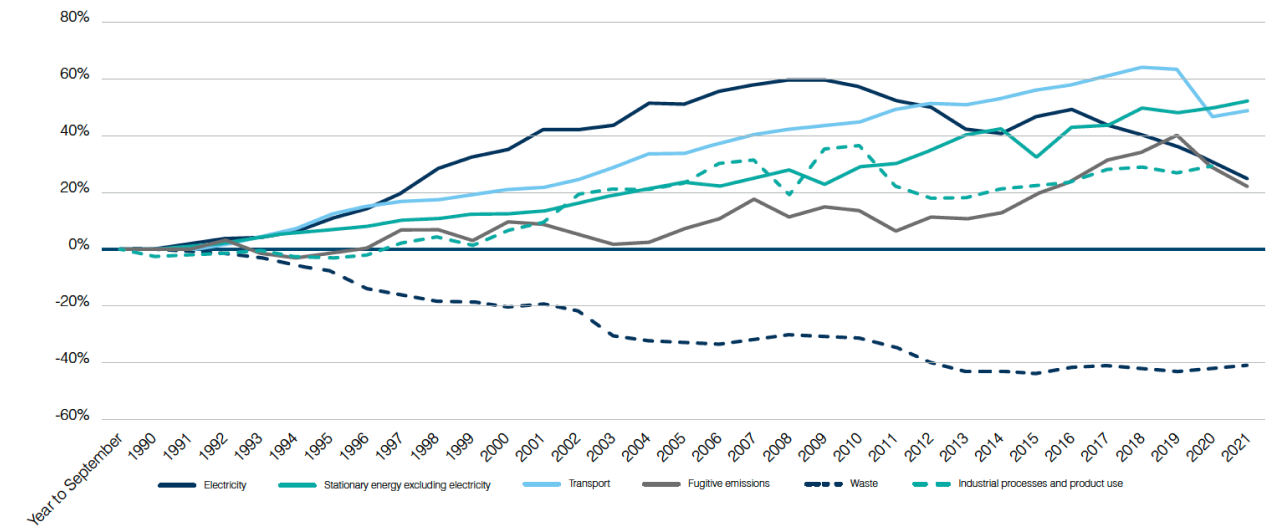

In Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory, carbon emissions in construction are spread across several broader categories, including in stationary energy, with emissions occurring from the direct combustion of fuels to use energy to manufacture materials like steel, as well as industrial processes and product use, with emissions for material production like cement clinker and steel.

“Fugitive emissions occur during the production, processing, transport, storage, transmission and distribution of fossil fuels. These include coal, crude oil and natural gas.”

– Australian Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources, Quarterly Update of Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory: September 2021

“Stationary energy excluding electricity includes emissions from direct combustion of fuels, predominantly from the manufacturing, mining, residential and commercial sub-sectors.”

– Australian Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources, Quarterly Update of Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory: September 2021

Australia’s share of total emissions, by sector, for the year to September 2021

Source: Australian Government Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources, 2022, Quarterly Update of Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory: September 2021

Energy

Gas’ share has increased from 18% in 2005 to 27% in 2021.

Renewable Energy’s share increased from 5% in 2005 to 8% in 2021. [3]

Australians for the past three years.[4]

wind (8.5%) and hydro (5.6%).[5]

Transport

Asset Lifecycle

FY2018-19.[9]

Percentage change in emissions, by sector, since year to September 2021 (excluding Agriculture and LULUCF)

Source: Australian Government Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources, 2022, Quarterly Update of Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory: September 2021

1. Energy is the first frontier of Australia’s decarbonisation

The path to decarbonising Australia’s energy system has been clear for many years: a renewables-dominated electricity system, backed by a diverse mix of storage technologies, and declining reliance on fossil fuels for energy in other parts of the economy. A low-carbon energy system is vital for a low-carbon Australia, and the sooner energy decarbonises, the easier Australia’s transition to net zero will be – but this must happen in an orderly fashion.

The good news is that we have the tools for the job and we know how to do it. Industry has been driving the transition at pace over recent years, and Australia has been installing wind and solar resources at a per capita rate ten times quicker than the world average. This has been driven by rapidly changing economics, with wind and solar having clearly surpassed fossil fuel-fired generators as the least cost sources of new supply. Energy projects have been added to the Australia New Zealand Infrastructure Pipeline (ANZIP) at record pace over recent years, with 100 renewable energy projects with an estimated total cost of $254 billion now under development or construction across Australia. The recent announcements of early coal plant closures for Liddell in 2023, Eraring in 2025, and Yallourn in 2028, are real-time examples of new low-cost renewables forcing out higher cost legacy fossil fuel generation.

The major challenge is completing this transition at least cost and with no disruption for energy consumers. This is where governments can do more. While state and territory governments are pushing forward with their own energy transition priorities and projects, and institutions, including the Energy Security Board and the Australian Energy Market Operator, are providing guidance, the absence of Federal coordination and leadership is the equivalent of boxing with one arm tied behind our back.

Read Chapter2. Emissions from the movement of people and goods have been rising, but transformation is around the corner

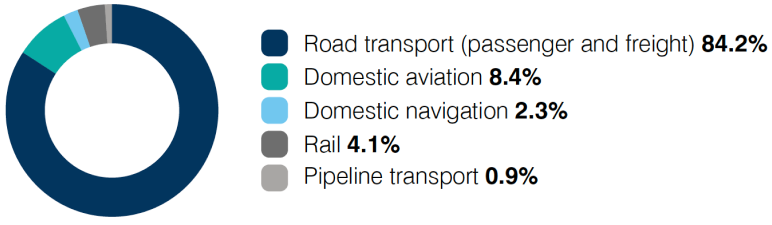

Despite improvements in vehicle efficiency over recent decades, Australia’s transport emissions have risen by 48.8 per cent against 1990 levels. But change is on the horizon, with the commercialisation of technologies that will underpin decarbonisation of public transport and light vehicles – of which the latter is consumer-led. Freight decarbonisation is on a slower trajectory, but there are clear steps governments and industry can take now to accelerate the change required.

In contrast to the gains made in energy, pre-pandemic transport emissions rose steadily from 9.7 per cent in 1990 to 19 per cent of Australia’s national total in 2019. There was a brief dip during 2020, but transport emissions have bounced back to make up 18.1 per cent of the national total last year. Actual emissions are likely much higher as well, given emissions from international aviation and shipping are excluded from these totals.

This upward trend reflects some of the challenges we face as a nation – vast distances between cities, production regions and markets, as well as a growing population with changing needs. But emerging technologies will turn this trend on its head. This is particularly true for light vehicles, which are on the cusp of a major transformation. Uptake of hybrid- and battery-electric vehicles is growing rapidly as their prices fall relative to internal combustion engine vehicles. The trajectory towards a low- to zero-emission light vehicle fleet is now all but certain.

Read Chapter3. Decarbonising assets through construction, operation and waste will require sustained innovation and reform

The final frontier of decarbonising the infrastructure sector requires a reduction in the emissions across asset stages – emissions embedded through construction, generated by asset operations, and left behind through waste. Compared to energy and transport, the technologies and methods required to overcome this challenge are the least developed. But with sustained commitment to innovation and reform, and by aligning incentives and investment opportunities with industry appetite for change, decarbonisation of the full infrastructure sector is possible.

The scope of emissions-related challenges in infrastructure has expanded rapidly over recent years, to a moment now where the carbon embedded within assets is in stark focus as an area for action. There has been some progress – largely industry-driven – through developments such as green concrete, recycled waste in construction materials, and pre-fabricated construction. But, up until now, embedded emissions across construction, operation, and waste have generally been a second order issue in dialogue on decarbonising the sector.

While Australia’s official carbon emission reporting does not account for construction emissions in its own standalone category, it is estimated that Australia’s construction industry generates 30 to 50 million tonnes of carbon every year.

Read ChapterContents

Unlocking a zero-carbon future for infrastructure construction

Decarbonisation of infrastructure operations can be accelerated

Improving waste management can unlock hidden avenues for decarbonisation

Harnessing ESG investment as a driver of change

Recommendations to decarbonise infrastructure construction, operation, and waste

Contact Information

Mollie Matich

Head of Policy and Research

Jon Frazer

Director of Policy & Research, Infrastructure Partnerships Australia

Boronia Blow

Head of External Affairs

Sign up for more Infrastructure Analysis

Sign up for our popular weekly Infrastructure Report newsletter and keep up to date on all the latest developments in the sector.

Sign Up